At SingLoud.org, we were saddened to learn of the passing of Buell E. Cobb, Jr. on April 26th. Although I never had the chance to meet Mr. Cobb personally, his books and writings have been a vital resource in helping me—and so many others—better understand and appreciate the Sacred Harp tradition. Through his work, he conveyed not only the history and musical structure of this tradition but also its spirit, its people, and its enduring meaning.

In recent months, we were fortunate to engage in some correspondence related to Mr. Cobb’s work and the efforts we have been undertaking here at SingLoud.org. His generosity in sharing his knowledge and his encouragement toward projects like ours are part of the broader legacy he leaves behind: a tradition kept alive not only in singing but in storytelling, reflection, and shared community.

In honor of Mr. Cobb’s life and contributions, we are sharing his essay, “The Sacred Harp: Rhythm and Ritual in the Southland,” first published in the Spring 1974 issue of The Virginia Quarterly Review (Vol. 50, No. 2). It remains a clear and evocative description of the Sacred Harp tradition—its sound, its setting, and the lives intertwined with it. We hope that sharing this essay will help others encounter or revisit his work with the appreciation it deserves.

Previously we published Buell Cobb’s “A Tradition Oblivious Of Modernity”, 1968, with his gracious consent.

THE SACRED HARP: RHYTHM AND RITUAL IN THE SOUTHLAND

By BUELL E. COBB, JR.

An old-time Sacred Harp singer, attempting to distinguish his special brand of religious folk song from other types of singing, leveled his eyes with his listener’s and spoke his mind. “Now all this modern stuff,” he said, “is more like aspirin, or calamine.” Gospel singing was what he was referring to, but he left room in his generalization for any other music similarly padded with accidentals—ear-ticklers, “painkiller.” Sacred Harp singers, on the other hand, “… sing by feelings,” he explained. “And we don’t need sharps or flats either.” What the old singer meant and what may serve here as an overall description of the Southern tradition he represents is that the Sacred Harp is—in tone, in musical effect, in the somber themes the songs focus on—an emotive and yet a deeply disciplined music, austere and uncompromised.

To a society that relies on painkillers and salves and sometimes more questionable palliatives, that prefers not to venture into the wilds without the “necessary” modern conveniences, the Sacred Harp adherents hold up, as in relief, a system of music and folk life that is somehow very basic. Theirs is an antique singing tradition that seems, by contrast with much of today’s rootless living, strangely fresh and vigorous—a music raw and elemental and genuine, not softened by accidentals or dynamics or any other kind of subtlety, but harsh to the modern ear, and yet rich and haunting as few other kinds of vocal music are.

The folk art of the Sacred Harp derives from three late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century American traditions: shape-note hymnbook singing, the New England singing school, and the revival camp meeting—traditions which fused and crystalized in the South with the publication of “The Sacred Harp” by two Georgians, B. F. White and E. J. King, in 1844. The volume’s “white spirituals,” in three- or four-part harmony (tenor or melody, bass, treble, and sometimes alto), were first performed at Sunday gatherings or at two- to four-day “conventions” in a form already initiated by the early American singing school and in a spirit not unlike the great camp meetings of the early 1800’s. From the turn of the twentieth century on, the sessions often took place at courthouses or municipal halls, but the real home of the singing has always been the country church.

George Pullen Jackson discovered the Sacred Harp phenomenon in the 1920’s, and his chronicling of the dwindling tradition and the songs on which it centered brought new life and awareness to the field of early American and Southern folk-hymnody. The kind of singing Jackson paid tribute so effectively to was once popular throughout the South, but it has now long been eclipsed by the commercialized blare of gospel music. For the most part, the songs have remained the possession of the Southern white, though there is a substantial tradition among blacks in an area of southern Alabama and northern Florida and in Texas, as well as a small satellite group in New Jersey. (The black and white manifestations of the tradition, in overall effect, are roughly equal, if still separate.)

A century ago the Sacred Harp participants overflowed not only the churches where they met, but the surrounding land as well. Records of the first renewed session of the Chattahoochee Convention after the Civil War show that it met at Pleasant Hill Church in Paulding County, Georgia, in 1866 with an attendance estimated at 8,000—a crowd which on the last hot day of the convention drank three wells dry. No such testimonial of strength exists today. Probably there are fewer than 8,000 Sacred Harp followers in the entire territory at the present. Still, in the areas where it has traditionally been favored, the Sacred Harp dies hard (there remain over 500 annual singings a year throughout the region). But although these singings often occur only short distances from some of the largest Southern cities, the Sacred Harp folk are separated from the life around them, in their singing practices and ritualistic music, by centuries and in deeper ways, in their attitudes and values, their joy in group singing, by more than years.

The most obvious separation, of course, is the discipline of the Sacred Harp, the folk idiom itself. And central to this is the singing of the shape notes. To incorporate a system for sight reading into their music, the authors of tune books like “The Sacred Harp” had depended on solmization—chiefly the well-established syllables fa sol la fa sol la mi fa (for the octave)—and, after 1800, shaped notes, which would help to link the appropriate syllables with the notes. Normally these training devices would have been dispensed with when the pitches to a piece of music had been mastered. But Southerners have always been lovers of form, and, along with other trappings of the singing school (at a singing each leader directs the “class” in a “lesson”), the Sacred Harpers retained and ritualized the singing of the shape notes, the text to the music being sung after the solmization.

In actual practice, especially on the songs with lively rhythm, the solmization becomes a blur of jargon. And although the singing of the syllables was conceived for a practical purpose—to “put the tune in mind”—the effect, and perhaps the ultimate appeal, is that of incantation. Sometimes called “the unknown tongue” by outsiders, the fasola-ing which introduces every song is performed neither lightly nor self-consciously. Rather, it “sets” the form and insures the special reality by which the singers relinquish themselves to the music and the sounded symbols, or to some deeper satisfaction which these provide. Beyond its practical use, the function of the solmization is the same as that of any ritual; it serves, as a frame does on a picture, to isolate and rarefy the vision.

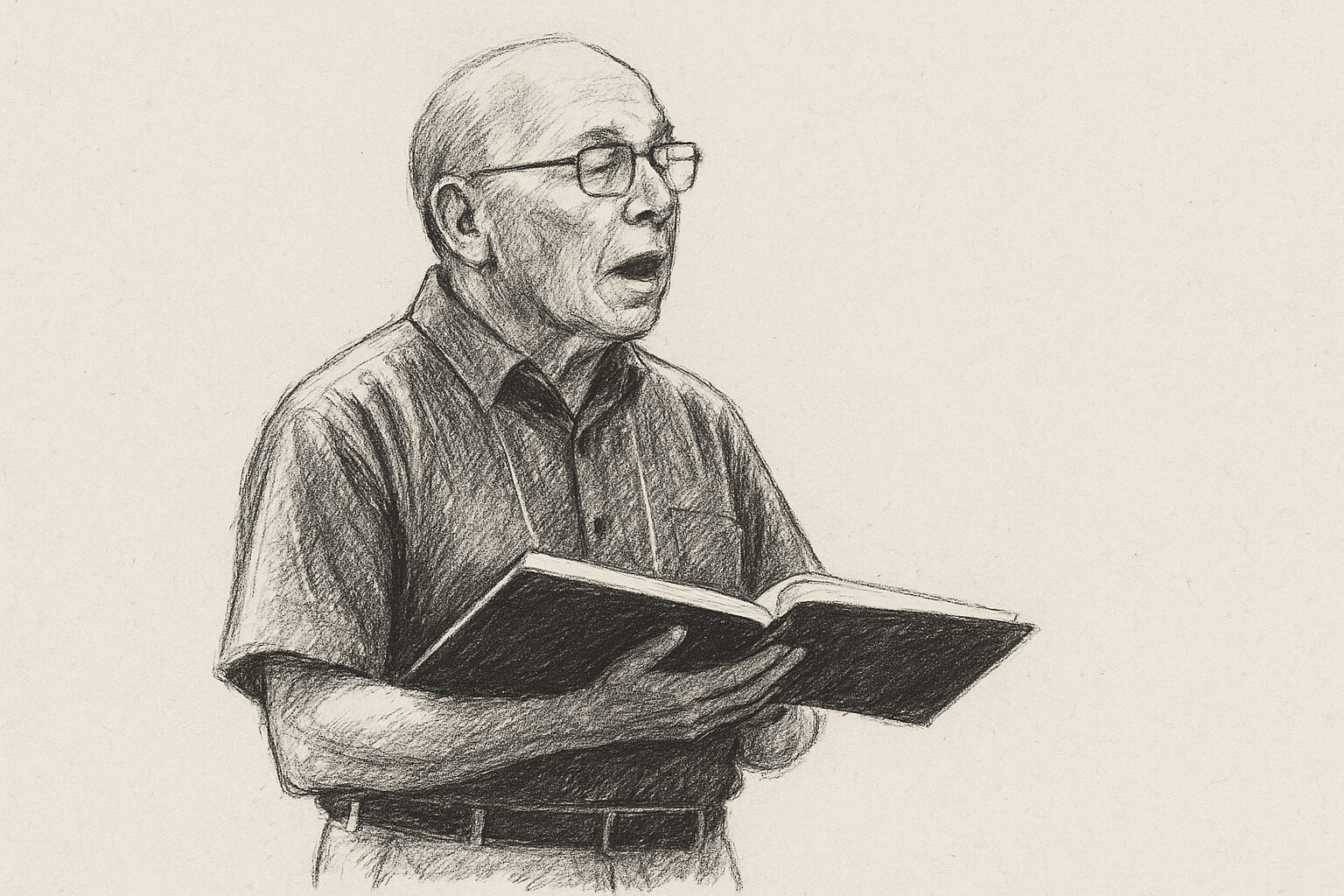

In the singing, the solmization and then the verses to the songs are performed with what is, by contemporary standards, a remarkable musical quality not always captured in available recordings: austere harmonies similar to organum; melodies sometimes rousing, sometimes plaintive; a heavy stamping of feet on the wooden floors; the steady rising and falling of hands keeping time; and a volume that billows and almost deafens as the singers warm to the music. Tapped by an “arranging committee,” who informally call out in turn everyone they see or know, the singers individually come before the group to select and lead their two allotted songs from over 500 tunes found in the book. Proceeding thus democratically, these singers fill the humble, box-shaped churches they sing in with a sound as large and as wise as a gothic cathedral.

The total effect is reminiscent of other sounds, but finally unlike any other—the tone harsh and strained, the rhythmic gait peculiar to these vocalists and their old-time music. The “fuging songs,” country cousins of the madrigal, create a cacophony of melody, as each part takes up a fragment of the tune to sing against the others. Much of the time the melodies are neither major nor minor, as the modern ear recognizes those tonalities, but instead are constructed on modal scales out of the medieval ecclesiastical tradition. Also many of the songs now affixed with harmony are tunes or tune fragments which had been orally transmitted for centuries and then set in the shape-note song books of the early 1800’s (“Wayfaring Stranger” and “Wondrous Love” are well-known examples.) Finally, voice doubling and the use of parallel fifths throughout give the harmony a primitive quality that strikes a deep responsive chord in both singers and listeners.

The way the singers pursue these effects is suggestive of something even more elusive. Although as a body they are deeply religious, they do not convene to fulfill “religious obligations”; they come because they love what they are doing. Overall, their gatherings are an unusual blending ofthe sacred and the secular. And when the singing has reached a certain level—when the singers respond wholly to the music—it is almost as if they are only receptacles, vessels for something age-old which lives again through them. As each new leader assumes his position in the middle of the square, the selections are drawn alike from the deep, rolling minor pieces and the old-style fuging songs that mesh the parts at breath-taking speed. The pace is rarely slackened, and upwards of a hundred songs—each with solmization and several verses—may be finished off in a day.

Throughout the music there is an uncommon emphasis on death and, in song after song, a disparagement of the vanities of this world. It must be admitted that most of the songs are not doleful; many of them speak purely of religious devotion, the joyful prospect of heaven, or even, as vestiges of the old Yankee sentiment, the glory of “freedom’s happy land.” Still, an awareness of the transience of earthly happiness pervades the collected verses. For illustration, witness the bittersweet “Bride’s Farewell,” quaintly remindful of how even in the midst of wedding mirth the sting of uncertainty may be felt:

Farewell, mother, now I leave you,

Griefs and hopes my bosom swell;

One to trust, who may deceive me:

Farewell, mother, fare you well.

And above all, the words to many of the tunes press the awareness of death on the “heedless youth,” as in the song “New Topia”:

Remember, you are hast’ning on

To death’s dark, gloomy shade;

Your joys on earth will soon be gone,

Your flesh in dust be laid.

The concern for mortality expressed in the Sacred Harp differs strikingly from the lip service paid to death in conventional society. Indeed, an accusation often made is that the American way itself is a pattern of escapism—a flight from death and reality by indulgence in work, pleasure, or illusion. It could be said, by contrast, that the sturdy Sacred Harpers bring their adversary into their midst; that in their bare, roughly hewn churches, they confront their demon, wrestle with it, and perhaps also exorcise it.

They are agrarians, these hearty singing folk. If they are not themselves farmers, pasture and field are at least part of their way of seeing. They are attuned to the seasons, to rain and crops and what the shifting wind can mean. With mutability thus imaged all about them, they mark the sure toll of time. And because of what they have come to know, they are not forgetful of the rôle they must play in the overall scheme. Most of the singers are from fifty to eighty years old, and their coming together each annual session is recognized by all as only another extension against that debt to which they must one day be called. Close by the church and the tables they will eat from are the graveyard and its staggered tombstones, bent with the drift of years. And for those who have returned for decades, the years of attendance show, like rings on a tree, the fullness of their time. For all their laughter, the enjoyment of company, the robust meals they join in, they are sobered to the reality their songs teach:

The living know that they must die,

But all the dead forgotten lie;

Their mem’ry and their sense is gone,

Alike unknowing and unknown.

The emphasis on death in the Sacred Harp songs might appear morbid to outsiders, but the Sacred Harp singers would be puzzled by such a charge. Theirs is a “ceremony of innocence.” They approach their music sternly and sincerely, with the kind of detachment, paradoxically, that comes from genuine involvement—like the Greeks, who had tragedy for popular fare because they found a cleansing wisdom in the hero’s fall, or the people of Spain, filling the arena so that in the bullfighter’s rigid pirouettes they might trick death and expiate their fear.

For the Sacred Harp adherents, music is spiritual power, and when music and death converge in the soaring harmonies of their songs, the singers may be purging themselves in a way that readies them for life. A story is told of one of the shape-note singers who was known for his strong preference for minor music over major. On one occasion, a friend quizzed him as to whether he thought there would be any minor music in heaven. “No, I guess there won’t be,” the old singer conceded with a grin, “but it’ll sure help you get there.” What welds the Sacred Harp singers to the tradition they have made a way of life is not simply the undeniable appeal of this lively music, but also the moral potency that stirs these people as they sing.

This may in part explain what to a neophyte seems the most startling incongruity of the singing: that the Sacred Harpers take up their songs with such obvious gusto, that they perform the most sinister lines to foot-stomping rhythms. (For analogues, one could recall the jazz funerals of New Orleans.) But if there is any unsettling incongruity in their performance, the singers are innocent of it. They are about a business whose rewards are, for them, as upright and true as the dusty pine walls that catch their songs and send them echoing back.

The Holly Springs Memorial Singing at Holly Springs Primitive Baptist Church, between the two small towns of Bremen and Carrollton, Georgia, is a typical Sacred Harp singing which takes place the first weekend in June each year. The activities of the 1972 session may be recreated in part here as an illustration of the unique characteristics the Sacred Harp gatherings display.

Around ten o’clock on the morning of the Saturday meeting, Buford McGraw, chairman of the singing like his father before him, calls the singers together with a song often used to open the sessions here since the first one in 1916—“Abbeville.” About one-third of the crowd which will number close to one hundred are seated already. Several more enter before the last slow strains of the song are sung: “. . . and unto Thee will I devote / The remnant of my days.” The chairman briefly welcomes the singers—most of whom are from this area in Georgia, a few from Alabama—and then turns the affairs of the day over to the arranging committee.

The entire church itself is made of wood—the benches, the ceiling, the unpainted gray-brown walls and floor. There is no organ here, no piano. And if there were, the singers would not use them. The organ, as it has done in congregational singing elsewhere, might relegate them to being only adjuncts in the overall service. Besides, with their strong harmony and independent rhythms, they need no instrumental help.

The singers are arranged in front of the podium of the church in the time-honored formation of a “hollow square.” Two benches for the altos are directly in front of the pulpit. The tenors, both men and women and many more in number, face the altos across the space provided for the leader. On the left side of the tenors are the basses; across from them, the trebles, also with mixed voices. As singers come in to fill the parts, they shake hands with all around them, settle back to the severity of the handmade benches, and spread the stout oblong books across their laps.

A cooling breeze would otherwise be welcome to these musicians, crowded around an open square, row on row, but they know that a sustained draft of wind would soon shut off their voices, and so they leave the doors closed, only stirring the air occasionally with cardboard fans. As each leader calls out his selection, there is a flurry of pages; the keyer of the music sounds a triad to establish the pitches; and, amid the vigorous beating of time with hand and foot, the song is commenced. From morning to mid-afternoon, the steady flow of music is interrupted only by a recess of five minutes every hour and at noon the socializing hour with dinner-on-the-grounds, when the singers wander down the long tables in the grove of trees, the women inviting favored singers to dip into their baskets of chicken and ham, corn sticks and pie.

On the second day of the singing, the sound, more than before, is loud and strong, as if vocalizing on the previous day has helped to open the throats of the singers more fully. All of the seats to the center are filled, the participants leaning forward to add their voices to the music. Their interest is of the moment. But one can see that, of the listeners, several of the aged of the community sitting further back among the benches are restored to the past by the power of these songs—their gaze projected elsewhere, their lips tracing some remembered melody.

Just before lunch, at the height of the singing, a quarter of an hour is set aside for the “memorial lesson,” a traditional observance in which the deceased of the past year are honored by song and testimony. The Sacred Harp folk are here acutely reminded of the loss of many of their number, faithful in the tradition, for whom there appear to be no replacements. Painfully concerned as the singers are for the continuance of the Sacred Harp even beyond their own knowledge of it, the list which is read at this time—often ten to twenty names in any given area—is like a bell that tolls the end of the singing itself. “We are passing away,” they often sing, and they feel this truly.

The “lesson” on this occasion is given by Mrs. Ruth Denson Edwards, whose father was a legendary teacher of the Sacred Harp from Georgia to Texas. Although Mrs. Edwards is considerably past the biblical allotment of years the Sacred Harp people often sing about, she and her octogenarian cousin, and his wife, have driven two hundred miles from their homes in Alabama for this session. Once close to losing both her hearing and her sight and surviving multiple operations in the fight to regain them, Mrs. Edwards appears indomitable. The years have not stooped her frame. And half a century of teaching elementary-grade children has made her a master of simple rhetoric. She speaks with emphasis, and her pauses are wells of thought. As the phrases flow, the long index finger of her left hand stays the crowd and punctuates her words. The audience, of all ages, is entirely in her grasp. Mrs. Edwards’ memorial lesson is reconstructed here by a listener who found her bearing and the conviction of her spontaneously worded address unforgettable:

When I was a little girl, I didn’t like the memorial lesson. (She speaks now for several of the young who are uncomfortable with this part of the service.) I thought it was sad, and I wanted to get out of the church. But my daddy said to me, “Babe, there’ll come a time when you’ll think that’s the sweetest lesson of all.” And that time has come. (Her voice softens to a whisper.) That time has come.

All of you under the sound of my voice (her eyes span the crowd) . . . will be touched by death, if you haven’t already. Death has touched me many times. The Death Angel has claimed two of my brothers and three of my sisters. I’m the last of my family of the Denson-Burdettes, and Bob there (pointing to her cousin) is the last of the Denson-Burdettes of his family.

For all of us—for all plants, all animals, for all forms of life—there’s a cycle . . . we’re only born to die. We go through four stages. After we’re born, we grow, we bear fruit (she waves her hands) . . . we age, and then we die.

When I was in college, I had to write a term paper in Psychology. And any of you who’ve ever had to do that know that it’s hard! (The listeners stir, faces smile.) And one of the things I read . . . was about the way people react to death. You know, any of you who have lost somebody . . . when you talk about it, you’ll talk all the way around it, without ever saying it. We say, “when he passed away . . .” or “when he left us . . .” We won’t say the noun “death,” because death is a condition.

But the word death means going home. Death is a door . . . to . . . what is it? . . . Joy (quoting the Isaac Watts text now), “And yet we dread to enter there.” But the idea of death doesn’t bother me like it used to . . . (and now speaking of Sacred Harp singers) If there is a heaven—and there is—we know they’re there.

The names of the deceased are mentioned again, with Mrs. Edwards commenting on those she knew. Mr. Lee Wells, a much-beloved, aged singer from Alabama, is remembered especially: “He was a smooth and a graceful leader. Just before he died, he sat up on the Davenette and sang three songs—just as smooth and clear as he ever sang. He couldn’t talk, but the Lord gave him voice to sing, and then he died.”

She remarks again that death is a “going home” and reinforces her point: Mr. Wells, near death, could sing. She calls out the song she will lead, “Fleeting Days.” Under her sure direction, the class sings with an effect that is not mournful, but measured and strong, with a full volume of sound:

Time! What an empty vapor ’tis!

Our days, how swift they are,

Swift as an Indian arrow flies,

Or like a shooting star.

Our life is ever on the wing,

And death is ever nigh;

The moment when our lives begin

We all begin to die.

There is, indeed, no painkiller here. The singers follow these dark words as unfalteringly as they pursue their modal melodies and spare harmony. And because the pain they sing of measures their own pain—their fears and intimations—this music fulfills them, like some ancient ritual that fuses life and art, theology and song. “We don’t need sharps or flats,” the spry old singer said. He was never more correct. At high moments in their singing, these sturdy traditionalists entertain a great reality, a simple vision conceived in rustic fellowship and affectingly rendered in a haunting, vigorous music.

Leave a Reply